The Radical Sixties and the Militant Asian Americans

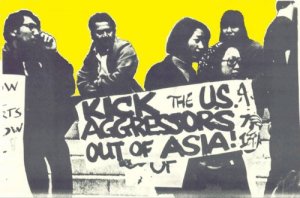

Fifty years ago, on March 8, 1965, the U.S. Marines landed in Da Nang, marking the beginning of the American ground war in Vietnam. Protests erupted all over the U.S., with the largest anti-war demonstration in the U.S.—the March Against the War organized by the Students for Democratic Society—taking place in April 17. Radicalism in the 60s has been the subject of social movement theories that set the direction of contemporary scholarship. But scholars in the field were remiss in examining a contentious group in American society: Asian Americans.

While Sid Tarrow was visiting Pittsburgh early this month, we had a conversation about the dearth of studies on Asian American mobilization, especially in the 1960s. In recent years, we have noticed a rise in scholarship on the Asian American movement (AAM). But based on a cursory look of undergraduate and graduate courses in social movements, Asian Americans remain invisible in mainstream discussions about the “turbulent 60s.” Cogent analyses of the AAM are still confined to area or ethnic studies. Daryl Maeda notes in his book Chains of Babylon: The Rise of Asian America the near-total absence of Asian immigrants and their children from the existing historiography on social activism in the 1960s and 1970s, which was also a crucial time for the formation of a radical immigrant identity. As we look back to the waves of protests in1965 and thereafter, it is important to recognize the crucial role that Asian Americans played in nearly every space of mobilization.

From mid- to late 1960s, broader political struggles such as the civil rights and the Black Power movement as well as changes in the internal demographics of Asian communities facilitated the birth of the AAM. The period was in fact the heyday of interethnic and interracial coalitions among Asians because of the unique domestic and international political contexts that shaped the ideology and resources necessary for coalition building. Within the framework of solidarity among colonized people, Asian Americans embraced a radical stance and coalesced with African Americans, Chicanos, and Native Americans. This coalition building contradicted the racial separatism that the New Left white activists have characterized the movement after 1968.

The interaction of international events—such as the American war in Southeast Asia, the Cultural Revolution in China, and the rise of the Non-Aligned Movement in the United Nations processes—and domestic realities—including the continued discrimination of Asians and the hegemonic discourse of Asians as “model minority”—promoted the construction and cultivation of a Third World identity. These political conditions profoundly influenced large numbers of minority youth to question the nature of American democracy and fueled militancy that was not couched in the language of civil rights. At the same time, the politicization of ethnic enclaves around a common grievance—marginalization of these communities in urban politics—laid the groundwork for future coalition formation. In the formation of AAM, the major participants included a new generation of Asian American students, who comprised the largest segment of the movement; impoverished community youth, both immigrants and U.S.-born, who lived and worked at the enclaves; and the old unionists and political and community activists from the earlier period, who had ties with the American Communist Party.

The ideological underpinnings of the nascent AAM combined anti-racism and anti-imperialism that did not fit into the “Bring the Boys Home!” mantra of established anti-Vietnam War groups. Asian Americans opposed the imperial ambitions of the U.S and expressed solidarity with the communists in Vietnam, who, in their view, were defending their struggle for independence and self-determination. They identified with the Vietnamese as Asian peoples in the American racial regime. Because of their articulation of racial commonality with the Vietnamese, Asian Americans felt alienated in the mainstream, predominantly white antiwar movement and found allies among other minorities, who were also demanding self-determination rather than integration. Thus, the origin and growth of the AAM was not based on civil rights frame but a Third World liberationist perspective. In essence, the movement that emerged among Asians in the U.S. was both domestic and transnational.

Asian Americans were not just active on international issues such as the Vietnam War. They were at the forefront of community struggles against corporate interests, as embodied in the movement against the eviction of elderly tenants of the International Hotel or I-Hotel in the Manilatown section of San Francisco. The I-Hotel was home to seasonal Asian laborers, a large majority of them were Filipinos. Inspired by the political slogan of Chairman Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, “Serve the People,” Asian Americans demanded that universities be accountable to their communities and students in the Bay Area joined the anti-eviction movement. Many of the Filipino American students who joined the movement were children of farmworkers and World War II veterans who participated in the Equal Opportunity Program (EOP) or went to college through special admissions for disadvantaged students. Their involvement in the anti-eviction movement led to the emergence of a working-class consciousness that betrayed the middle-class dreams of their immigrant parents (Habal 2007).

Asian Americans were also involved in the fight for the establishment of ethnic studies. In 1968, the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF), a coalition of the Black Student Union, Mexican American Student Coalition, Latin American Student Organization, Pilipino American Collegiate Endeavor, Intercollegiate Chinese for Social Action, Asian American Political Alliance, and Native American students, held a series of strikes at the San Francisco State College to demand the teaching of the histories, struggles, and triumphs of their people on their own terms. From 6 November 1968 to 21 March 1969, the TWLF mobilized thousands of students at San Francisco State College and led the longest student strike in U.S. history. They demanded the establishment of a school of ethnic studies with a faculty and curriculum to be chosen by people of color, along with open admissions for all non-white applicants. The strike was triggered by the suspension of George Mason Murray, a graduate student in English and part-time instructor in the EOP who was also the minister of education of the Black Panther Party. During the strike, the TWLF issued fifteen nonnegotiable demands, which included the reinstatement of Murray. The strike eventually resulted in the establishment of the first and only school of ethnic studies in the U.S. (Maeda 2009).

To support the TWLF, the inchoate AAM drew resources from the students’ ethnic communities—the Nihonmachis (Japantowns), Chinatowns, and Little Manilas (Liu, Geron, and Liu 2008). However, the resources that AAM could tap differed from the civil rights movement. Resources were limited to a few churches and social service organizations. In radicalizing these enclaves, the AAM drew from its explicitly antigovernment stance, strong sentiments for self-determination, and the radical transformation of society, which, in the context of the continued marginalization of these communities in urban politics and the significant strides of people of color in the civil rights era, resonated among the residents. The enclaves were not just a center of commerce and a hub for the propagation of cultural heritage for new immigrants. More importantly, they were historical communities where dense social ties exist among the people who share a common fate as racialized minorities. Hence, they shaped immigrants’ political identities, which were more than labels such as “immigrants” or “minorities,” but rich and textured understandings of themselves linked to families, neighborhoods, and particular histories.

After the glory days of the 1960s, the Asian American community changed dramatically. Within the AAM, revolutionary formations with substantial Asian membership began to dissolve in the 1980s. The effect of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 started to manifest itself in the community in the early 1980s, as professionals migrated in large numbers. Despite the demise of the organized Asian American left, community and organizational networks persisted and the legacy of the militancy of the 1960s remains alive. It would be an injustice not to learn about the Asian American movement in this important period in U.S. history.